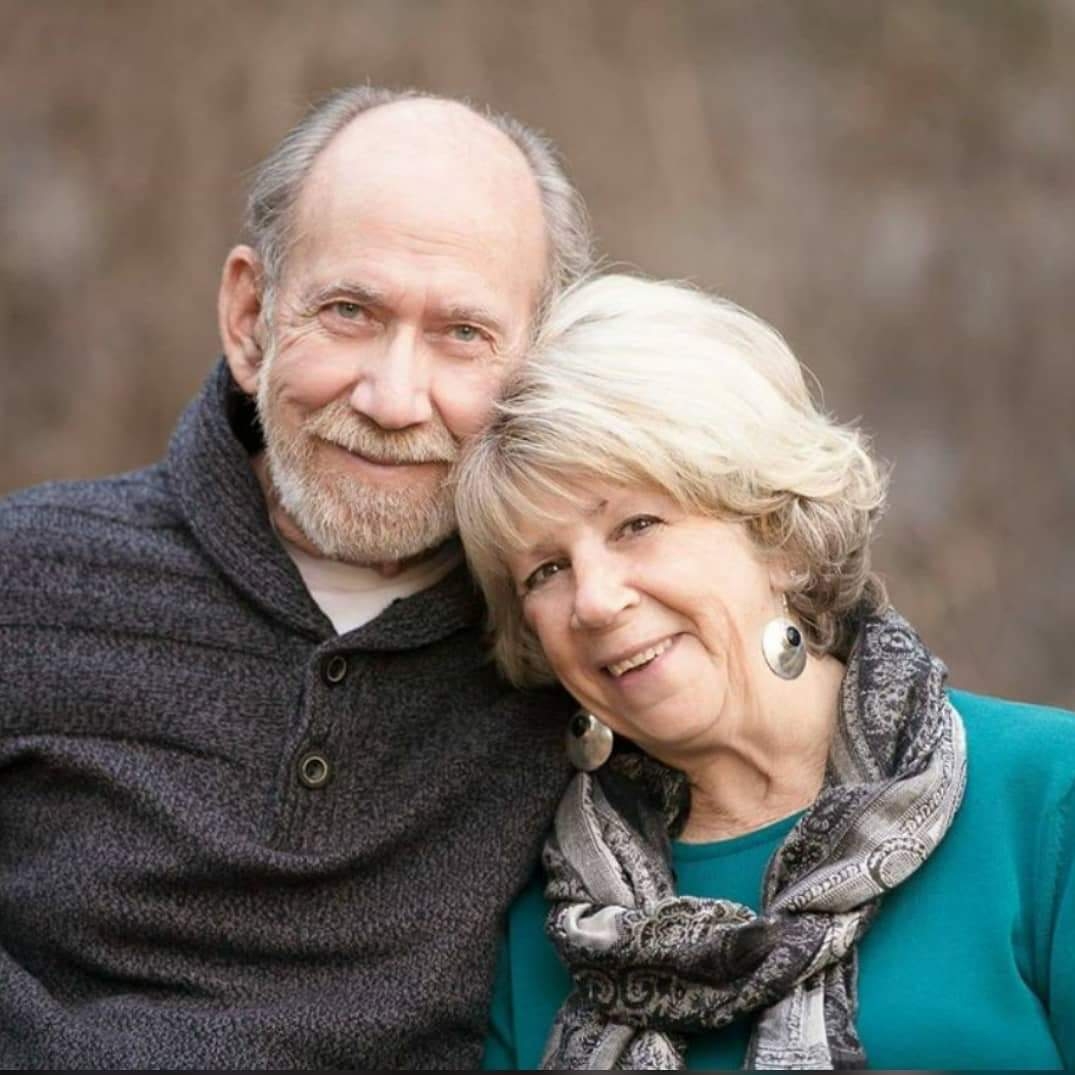

Lynn Lane shared her story in March of 2023.

After my husband’s death, I thought: Is this the way Richard wanted to die? Is this the way I wanted to see him die? No!

When you know you’re dying and you don’t have an option to live, you should at least be given the option of how you die. I learned about medical aid in dying only after Richard’s death, but if I had known about it, I would have taken him to Oregon (where the option of medical aid in dying has been available for over 20 years) myself, though no one should have to leave their home to secure a gentle passing.

My husband was an above-average healthy man. In the 54 years we spent together, I don’t even recall him ever having a headache with the exception of once. It was a shock when he was diagnosed with metastatic bladder cancer. He passed away just 136 days after being diagnosed — less than five months.

I met Richard in 1966; we married the following year in June and started our family two years later. What drew me to him was his dry, witty sense of humor that everybody who knew him loved. If I was stroking his shoulder he would say, “I’ll give you an hour and a half to cut that out.”

We enjoyed a very happy and active life together. Among our most gratifying endeavors was running our own hot air balloon company for 15 years. Then in 2000, with Richard’s thirst for adventure and exploring, we retired from ballooning, and he had a custom eight-passenger dune buggy built and offered off-road dune buggy tours to various local attractions. Our dune buggy business was awesome, but we weren’t in an ideal location for that type of business, so Richard retired just a few years later.

Frustrated by the miserable Arizona summers, in 2009 we saw an opportunity for adventure and relief from the dry heat. We bought a 36’ fifth wheel and hit the open road to enjoy America’s National Parks. Year after year we signed up for spring and summer job opportunities, working in the visitor centers of National Parks. This allowed us to explore the Oregon caves of Crater Lake National Park, the Redwoods, the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone, where we spent most of our time. We hiked nearly daily, and Richard would soak up as much knowledge as he could by attending seminars about the parks and the species that inhabited the natural area. We were staunch supporters of our National Park system, and Richard became enamored with the gray wolf recovery effort. After his death, we asked that loved ones make donations in his memory to The 06 Legacy, a nonprofit he loved that focused on the peaceful coexistence and long-term recovery of wolves.

But in August of 2020, our life slowed down after Richard contracted COVID. He was hospitalized and struggled to regain his strength after he was released. We skipped a winter trip to Texas to allow time for him to continue recovering and made plans for a spring and summer job at a Utah campground. We said to each other, “Well, at least we dodged the Big C.” Little did we know what lay ahead.

In March 2021, on our way to Utah, Richard complained of pain in his groin the whole drive and could hardly walk. Thinking it was just a muscle issue, he made an appointment with a sports medicine doctor. After multiple scans, the doctor told him he needed to see an internal medicine physician. We did as told, and after a battery of tests, we got the dreaded news: “You have cancer. You need to get home and start treatment.”

We had just started the job, but we had a real emergency we needed to manage. We returned to Arizona on April 1 and saw an oncologist just three days later. The oncologist told us he thought it was bladder cancer, but he was perplexed — he had never seen bladder cancer metastasize to bones. After numerous tests and scans, the doctor confirmed it was urothelial bladder cancer and started Richard on chemotherapy right away, hoping to give us two more years together. Without treatment, he estimated Richard may have four months.

The infusions were hard on Richard’s body. It wore him out and brought his platelets, white blood cells and red blood cells to startling low numbers. They would give him blood transfusions, his numbers would go back to normal, but within a week or so we’d be back in the hospital. His bones were so brittle from the cancer that in May he broke his upper left arm just by rolling over in bed. May and June consisted of 911 calls and ambulance rides, and we spent much time in and out of emergency and hospital rooms.

Richard grew weaker and weaker, and at the end of June, while at an infusion appointment, he was admitted to the hospital due to a high fever. Once again, his blood counts were at rock bottom. Richard’s body could no longer endure the demanding treatment. He and his oncologist agreed that it was time to enroll in hospice.

Richard returned home on June 27 with the support of hospice, who were helpful and reassuring. The hospice nurses told us cancer in the bones was excruciating and tried hard to stay ahead of his pain. But even with their instrumental help, my husband suffered greatly.

Richard was such a strong man, but the nurses were right — his pain was excruciating, and he’d cry out in agony. He kept praying for God to take him. He didn’t want to remain in pain. He was ready to die. Hoping to provide him some comfort, our cherished pastor administered to him, and regularly as we waited for the pain medications to take effect, our family would recite specific bible passages to Richard, and he would repeat them.

The past months had been grueling, and Richard’s last six weeks were even more harrowing. We could do nothing to provide him the comfort he really needed — a gentle passing. Instead, we had to watch his slow and agonizing demise.

My husband’s final weeks felt like a disgrace to his beliefs, to our beliefs. We believed that God is merciful and doesn’t want people in unnecessary pain. God doesn’t want people to suffer. People deserve autonomy at the end of life and an option to avoid prolonged suffering. Richard finally escaped his pain when he passed on August 8, 2021.

If medical aid in dying had been available to him, I am confident he would have accessed the option to ease his suffering. He knew he was dying, and his last weeks were full of agony; he couldn’t eat, he couldn’t drink, and he was in relentless pain. His death did not honor the loving and kind person he was. He deserved better, and I promised myself then that I would do what is within my power to ensure no one else is forced to endure what he did.